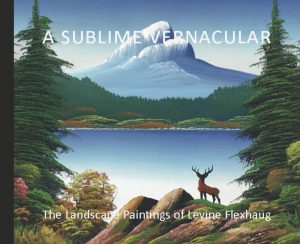

A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug

Levine Flexhaug

A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug

September 6, 2016 - December 12, 2016

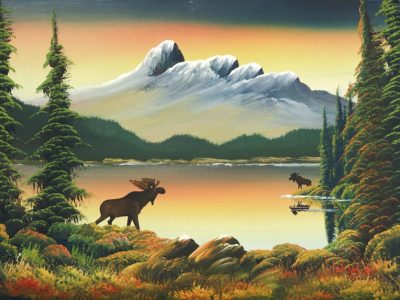

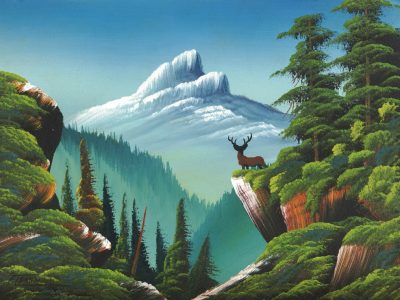

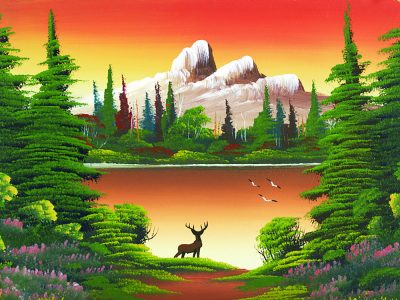

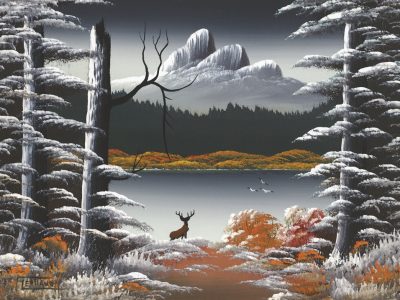

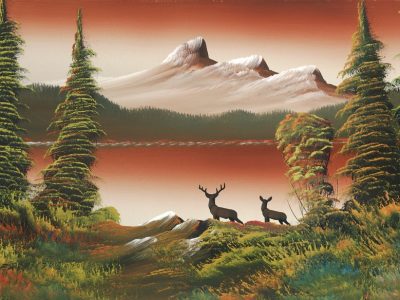

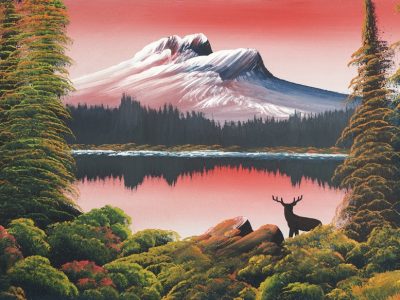

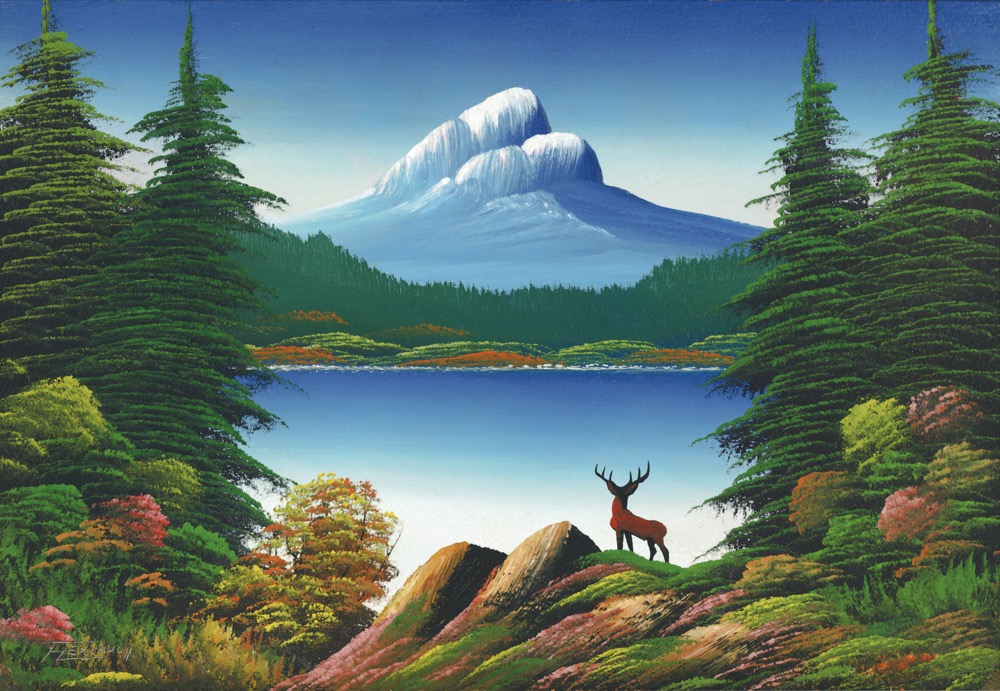

This incredible exhibition offers the first overview of the extraordinary career of Levine Flexhaug (1918 -1974), an itinerant painter who sold thousands of variations of essentially the same landscape painting in national parks, resorts, department stores, restaurants and bars across western Canada from the late 1930s through the early 1960s.

Whatever its variation, a Flexhaug image represents a Western icon, a silent unspoiled Eden that encapsulates the conventions of sublime and picturesque landscape painting in a kind of painter’s shorthand.

About The Artist

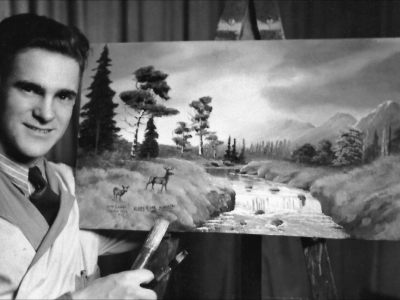

Born in Climax, Saskatchewan in 1918, Flexhaug, who signed himself “Flexie,” worked in the prairie provinces and in British Columbia, where he died in 1974.

The exhibition features some 450 paintings and will tour nationally following its presentation in Grande Prairie.

EXHIBITION DATES

MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan

May 23 – August 9, 2015

Illingworth Kerr Gallery, Alberta College of Art and Design, Calgary, Alberta

October 29 – December 5, 2015

Art Gallery of Grande Prairie, Grande Prairie, Alberta

September 6 – December 12, 2016

Rodman Hall Art Centre, Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario

January 21 – March 12, 2017

Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, British Columbia

July 14 – September 3, 2017

A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug is organized and circulated by the Art Gallery of Grande Prairie with support from the Museums Assistance Program of the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Curated by Nancy Tousley and Peter White

FLEXIE! ALL THE SAME AND ALL DIFFERENT

View the Youtube video here

PRODUCED AND DIRECTED BY: Donna Brunsdale and Gary Burns

FLEXIE! ALL THE SAME AND ALL DIFFERENT: 2015, 84 minutes, digital video

SYNOPSIS: Flexie! All the Same and All Different investigates Levine Flexhaug’s paintings by focusing on the role and significance they have for those who collect them contrasted with how his contemporaries in rural western Canada have understood and valued them. What emerges is not the typical biographical documentary, but a revealing exchange of ideas about the popularity and meaning of landscape painting and the position of Flexhaug’s work within the world of art, as well as a portrait of the disappearing milieu in which he painted. In the course of making the film, the filmmakers traveled widely in western Canada and elsewhere to conduct interviews with family members, acquaintances, collectors, art historians, and critics and visit sites and locations where Flexhaug painted and sold his work.

GARY BURNS

Gary Burns’s feature film credits include The Suburbanators, Kitchen Party, waydowntown, A Problem with Fear, and the feature documentaries Radiant City and The Future is Now! He has won numerous awards for his films including Best Canadian Feature Film at the Toronto International Film Festival for waydowntown. Radiant City, which he co-directed with CBC journalist Jim Brown, won the Genie for Best Documentary.

DONNA BRUNSDALE

Donna Brunsdale works in photography and film. Her photography work has been shown across Canada and is held in public and private collections. Her films include Moments of Despondency and Cheerful Tearful. She has taught film and visual art at the University of Victoria and the University of Calgary.

For inquiries or to purchase the film, contact Gary Burns: burn10@telus.net

THE BOOK

Published on the occasion of the first comprehensive exhibition of his paintings, A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug is a 160-page book that features 121 colour reproductions of Flexhaug’s paintings, historic photographs, interpretative essays, and an extensive chronology of the artist’s life.

The essays in the book explore the critical significance of Flexhaug’s art, his relationship to the tradition of ideal landscape painting, the Prairie influence on his art and career, and his place within both the history of “market-driven” art and the tradition of Canadian landscape painting.

A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug is published by the Art Gallery of Grande Prairie in association with Figure 1 Publishing of Vancouver.

Contents

Introduction: There was Magic in his Brush

Peter White

Levine Flexhaug and the Ideal Landscape

Nancy Tousley

A Mountain Fantasy’s Prairie Roots

Peter White

Making Art for the Market: Flexhaug in Context

Wayne Morgan and Sharilyn J. Ingram

Imaginary Postcards: (Flex)ible Storytelling of a (Lost and Found) Canadian Mythmaking

Elena Lamberti

Chronology

Nancy Tousley

Contributors

Nancy Tousley is an art critic, arts journalist, and independent curator. She was art critic of the Calgary Herald for more than thirty years and has been a contributing editor of Canadian Art since 1986. She has organized exhibitions for public art galleries across Canada. In 2011 she received a Governor-General’s Award in Media and Visual Arts for her contributions to contemporary Canadian art. She lives in Calgary.

Peter White is an independent curator and writer. He has organized exhibitions of contemporary and historical art for public art galleries in Canada, is author of It Pays to Play: British Columbia in Postcards – 1950s-1980s (Arsenal Pulp Press, 1996), and co-editor of Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007). He lives in Montreal.

Wayne Morgan is a former curator/director of the Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan. He currently lives in Grimsby, Ontario, where he conducts research and actively pursues projects in popular culture.

Sharilyn J. Ingram is on faculty at the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts at Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario. She came to academia from a career in cultural management, including senior positions at the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Saskatchewan Western Development Museums, the National Museums of Canada, and Royal Botanical Gardens (Canada). She lives in Grimsby, Ontario.

Elena Lamberti teaches North American Literature and Media Studies at the University of Bologna, Italy. She has published essays on English and Anglo-American modernism as well as Anglo-Canadian culture of the late twentieth century. Her book Marshall McLuhan’s Mosaic: Probing the Literary Origins of Media Studies (University of Toronto Press, 2012) was a finalist for the 2013 Canada Prizes. She lives in Bologna.

Quotes

Flexhaug’s performance revealed his process of image making and conjured its magic at one and the same time. His paintings offered their viewers an engaging, perhaps even mentally steadying, focal point, a verdant oasis for the eye and mind. They were a refreshing if mythical retreat from the trials of drought, the Depression, and war.

Nancy Tousley

Though Flexhaug began to work as an artist during the Depression … his career played out during the recovery and growing prosperity of the post-war years, a period in which old ways lingered even as the Prairies were recast in terms of modernity and modern life. … his experience provides an invaluable pathway through some of the lesser known but vital social history of the region with which it is intertwined.

Peter White

Flexhaug implemented the Four Ps of marketing – product, place, price, promotion. His product proved appealing to a wide range of people, for whom it would often be their only work of hand-made art. …In pricing his product, he clearly understood his target market: $5? $10? While his promotion might seem rudimentary in relying on direct selling and word-of-mouth, it worked – he apparently sold whatever he produced, and he continued to sell over a relatively long period of time.

Wayne Morgan and Sharilyn J. Ingram

Flexhaug’s paintings hung in a variety of places (restaurants, cafes, bars, hotels, people’s homes, and more) and grew into a peculiar landscape themselves: they became part of an everyday scenario reminding people of what Canada should (ideally) be.

Elena Lamberti

RECOLLECTIONS

Those who knew Levine Flexhaug or watched him paint are invited to share their recollections and reflections. We also welcome comments on his paintings and his practice. To share your thoughts, email info@aggp.ca.

This section is launched with a “memoir” by Wayne Morgan. A former Curator/Director of the Dunlop Art Gallery in Regina, Saskatchewan, Morgan first became aware of Flexhaug as a teenager in Weyburn. Here he discusses the impact of his encounter with Flexhaug’s paintings and their relationship to both the history of western Canada and the visual arts in Saskatchewan.

WHY DO I LIKE THIS?

Searching for the Past in Collecting Flexhaugs

Wayne Morgan

As far as I know, I was the first person from the art world to take an interest in Levine Flexhaug. During my fifteen years as Curator/ Director of the Dunlop Art Gallery in Regina, I bought my first Flexie at a small antique shop in the 1970s … perhaps attracted by vague memories, perhaps looking at it through a lens of Pop culture or irony, perhaps considering it a part of the research into regional culture that was informing many of the exhibitions I was generating at the Dunlop. Then I bought another, and another … and today I own nearly one hundred.

Trying to understand why I am attracted to this work takes me back to my personal history and to the history of western Canada.

I grew up in Weyburn, Saskatchewan – a prairie town renamed “Crocus” in W.O. Mitchell’s Who Has Seen the Wind. When I was in public school there was a kid in my class who could paint sunsets, the amazing colours that dominated our skies each evening. But it was the only thing he could do in art class … maybe because a sunset is so abstract and does not require any drawing.

My father had been in RCAF Coastal Command during World War II. He came home from the war with this bright painting on paper of a sunset against which an airplane is silhouetted. It had been done by a guy in his squadron who would whip off a sunset painting, throw in a plane taking off, and then give it away. He did them for everyone just as my public school friend did for us.

This is a kind of shorthand formula painting, an easy blending of colours that gives an illusion of reality. No skill is required other than the back and forth gesture to blend colours — and it is what Flexhaug did.

When I was about twelve years old I saw Levine Flexhaug painting in the window of Pittman Electric in downtown Weyburn. This was the first time I had ever seen anyone actually making art. As a kid I liked to draw, but there were no art teachers and all I could do was copy what I saw around me … advertisements in Maclean’s, comic strips, and a few science fiction magazines. I was good at drawing Little Lulu and Henry because they were easy to imitate. The sci-fi magazines drew upon the Yves Tanguy paintings of the day that made contemporary art look easy. I think I won an art award at the fair imitating Yves Tanguy.

But this guy painting these small pictures of trees and a lake and mountains.… It was so cool, all green and blue, so fresh and pretty. I wished I could do that.

At about this time our family took our first long trip with my cousins and aunt and uncle to Glacier National Park all the way across Montana. No more Regina Beach or Carlyle Lake — it was the Rocky Mountains that drew prairie people on their first real vacation. “Mom, they’re so big!”

We did not get a TV until a couple of years later. Then I got to see Jon Gnagy’s Learn to Draw. Gnagy, I would learn later, was a pioneer in art lessons on TV. He had this ‘artiste’ van Dyke beard and drew simple scenes with lots of curves and winding roads and barns and cute landscapes that had nothing to do with the gridded landscape of south-east Saskatchewan.

I thought about all of this when I found a 10 x 14-inch Flexie in an antique shop about 1977.

I also thought about my experience as a pilot project for the Saskatchewan Arts Board in 1968. After my art studies with Ken Lochhead et al. at Regina College, I returned to Weyburn as Canada’s first community resident artist. I set up art classes in towns like Creelman and Radville, where I learned to my surprise that virtually every adult with an interest in art was painting pictures of mountains and lakes. I told them to paint what they knew, so on my bad days I feel personally responsible for the plethora of images of abandoned barns and farmhouses.

I had been directing the Dunlop Art Gallery at the Regina Public Library since 1970. Things were going well. I was part of the first generation of artists and curators who chose to be part of the world while staying in Saskatchewan. We would contribute to Canada from here. And it was very important to all of us that we understand what “here” was … to retrieve the past that was shaping us, to uncover the stories, and to share it with the public. At school we had studied the history of elsewhere, and we needed to learn our own.

For many of us, folk art was a starting point. Our grandfathers had been the first to break the land, and we were in touch with settlement through our families. Folk art made this history immediate and palpable, and allowed me to bring the past to the present through exhibitions of folk artists, both painters and modelers. Folk art, quilt making, weaving and dyeing from local plants, documentary photography, the current and past history of pottery, the decorative arts of the prairie kitchen – all emphasized that we are here, we have a history, and don’t you dare just fly over Saskatchewan anymore.

With my own background in studio art rather than the academic study art history, and working in a gallery that was close to the public because it was part of a library, I felt I had a license to explore what I uncovered and thought important for the public to see. Exhibitions became tools for community awareness, and the artists in Regina shared my enthusiasm for these explorations.

But there was something else … the fresh air of the 1970s, feeding off the 1960s. There was a new freedom to like kitsch, collect knick-knacks, read comics, and admit that everyday popular culture could be a lot of fun while pursuing “high art.” In Regina popular culture was feeding the local artists and my exhibitions were an important source for them … exhibitions of comics, pinball, illustration art, wildlife sculpture, and whatever.

In our personal lives, the lack of affordable good design and our modest incomes led us to rely on taste and semi-competitive foraging to furnish our homes. Like my friends, I shopped at the Salvation Army and any antique store that could provide something that was better designed and cheaper than at Simpson’s or Eaton’s. Without an IKEA, you had to have some skill in sorting out furniture and decorative art, and the absence of good design left us with irony and kitsch as a survival mode.

So … haunting the antiques stores of the day, I found a Flexie. Suddenly I was thrown back in memory to a cabin at Carlyle Lake, to a house somewhere I could not precisely remember, and to the window of Pittman Electric. It struck a chord deep within me.

It also stirred feelings about my parents and aunts and uncles who as young people survived the drought and the Depression. When they saw this wonderful green and mountainous image, it was so refreshing, so dreamy … a refuge from the tensions of their past. In the 1950s when they could afford a rye and ginger on a holiday, they never cried about the poverty and bleak future of their younger days. They laughed and laughed.

These calm cool paintings evoked the unfulfilled promise of our parents’ youth.

At five bucks, I thought, this painting is a connection to my past, and just a sweet little picture from a guy I saw paint in Weyburn.

I installed my first Flexhaug in my living room. After openings at the Dunlop I always had parties at my home, and people who saw these little mountain pictures growing on my walls started to say, I remember that. Terry Fenton (curator, director and artist) – whom I have known since the mid-sixties when Ron Bloore hired him to assist at the MacKenzie Art Gallery – stated he had bought one at Simpson’s in Regina as a present for his parents when he was about twelve. Richard Spafford, a local collector and antiquarian book dealer, remembered Flexhaug painting at Waskesiu National Park in northern Saskatchewan – a memory shared by Saskatchewan-born New York sculptor Robert Murray, who remembered that for an extra twenty-five cents the artist would add an elk to the landscape. The Governor-General’s Award-winning poet Patrick Lane surprised me with his memories of Flexie on the B fair circuit in the interior of British Columbia. In every case the experience was the same: this was the first time I saw an artist making art.

In 1985 I moved to a new position at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, and I installed my growing Flexhaug collection in rows on a wall at the foot of my bed. Every morning I stared at them – all the same subject, all the same size – and asked myself, why is this interesting? When I saw the contemporary artist Francis Alÿs’s installation of hundreds of near-identical portraits of Saint Fabiola that he had collected at the National Portrait Gallery in London in 2010, I recognized a kindred spirit – although I have not found Alÿs to be any more articulate on the fascination than I am.

When I left the West for Ontario, I had an arrangement with my old friend Richard Spafford, who often dealt with collections and estates. He would scout for Flexhaugs for me; if they cost more than five dollars I had to pay him, and if they cost less than five dollars they were a gift. This worked well for a few years, but then the prices rose substantially as pickers assumed there was a market. My collection continued to grow more slowly, through the occasional purchase and gift (from family and friends who knew I would always consider a Flexie the perfect present). Then in 2007 I received a phone call from my brother-in-law Wayne Ingram from a Red Deer antique mall with a Flexie alert: almost fifty works! By now a hopeless completist, I bought them all, sight unseen.

I was not merely collecting – I was also eager to share my research. I first articulated my insight into Flexhaug painting as sanctuary in a 1987 paper presented at the joint annual meeting of the Popular Culture/American Culture Associations in Montreal.1 Then in 1995 I had the opportunity to really examine the oeuvre since many others had now also acquired these works. Expanding the rows of works that had so engaged me in Winnipeg, I had sufficient range for serious analysis of the works, resulting in a striking installation wall at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in the exhibition Welcome to Our World: Contemporary Canadian Folk Art.2

My reflections at this point: my response to Flexhaug is deeply tied to my personal history and the history of the part of Canada where I am from. I can see young people’s yearnings and dreams of a better world in those mountains and trees, painted by someone who shared these dreams and used his limited talents to realize them.

Recently I found a quote by novelist Milan Kundera that spoke to me: As soon as kitsch is recognized for the lie it is, it moves into the context of non-kitsch … becoming as touching as any other human weakness.

I think of my parents’ struggles, and I understand Levine’s. They came through to the other side, dreams a bit battered but able to enjoy some simple pleasures … a beer and a $5 painting.

- P. Morgan, “Flexie: The Popularity of a One Scene Speed Painter on the Canadian Prairie, 1935-1965,” (presentation, joint annual meeting of the Popular Culture Association and the American Culture Association, Montreal, QC, March 25-27, 1987).

- Susan Foshay, Pascale Galipeau, and Nancy Tousley, Welcome to Our World: Contemporary Canadian Folk Art, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, ON, September 14, 1996 – January 12, 1997.

- Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Part 6, quoted in Tomas Kulka, Kitsch and Art (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996), 107.