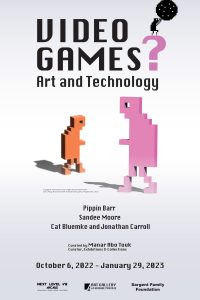

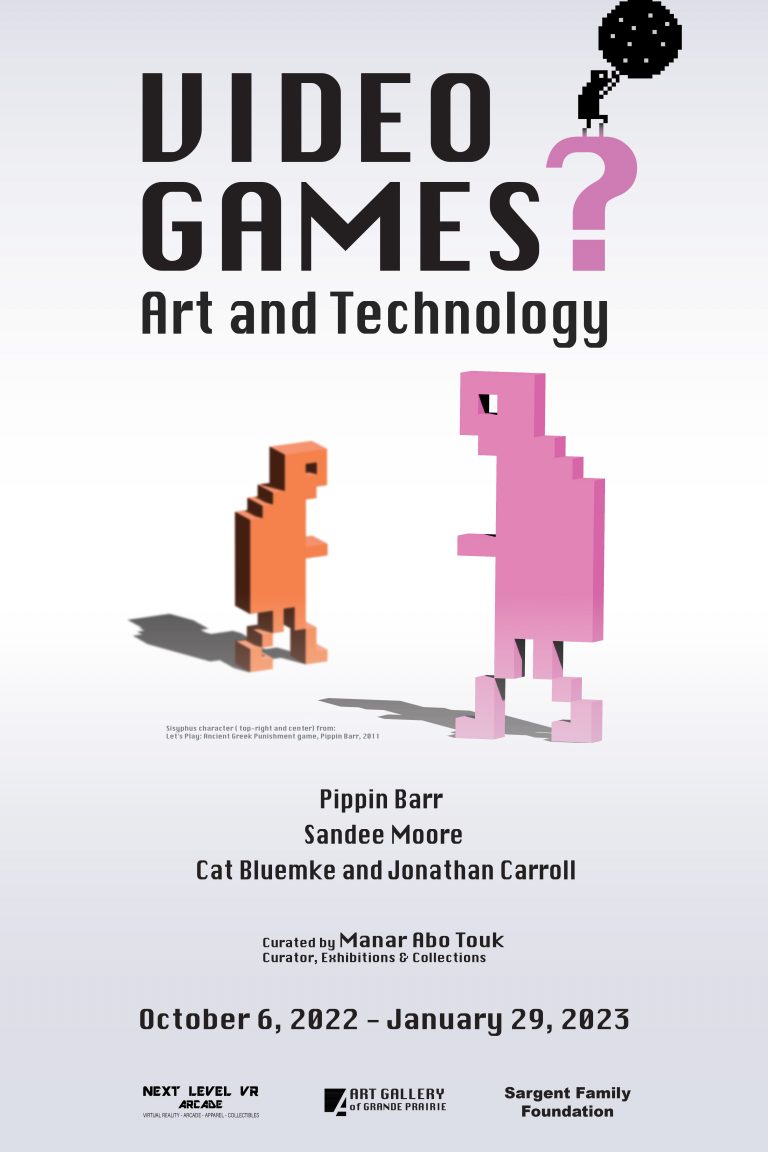

Video Games? Art and Technology

Video Games? Art and Technology

October 6, 2022 - January 29, 2023

Video Games? Art and Technology is a group exhibition featuring Pippin Barr, Sandee Moore, and artist collective SpekWork (Cat Bluemke and Jonathan Carroll), that examine video games as an artform for design and self- expression. From computer art to digital art, to animation, web-based art, photography, film, AR and VR, and video games. The Art and Technology movement of the 1960s provided artists the tools to mix technology, art, and science.

As technology advanced and progressed, gaming design grew as an artistic practice. In the 1990s digital artists explored the historical dimension of the computer and its development as a creative medium. Video Game creation allows artists to play with technological tools and game mechanics to question our perception of the physical world. How can Video Games shape and contribute to the way we learn history and understand issues in the contemporary world? such as the representation of female skateboarders, architecture and labour, or philosophical mythology.

Video Games? Art and Technology aims to create a digital artistic experience that reflects on how technology and art are used to examine design structures and societal themes through re-interpreting classic video games and offering a new way of seeing in our digital age.

Curated by Manar Abo Touk, Curator, Exhibitions & Collections

Click to enlarge the exhibition poster

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Pippin Barr

ARTIST BIO

Pippin Barr is a videogame maker, educator, and critic who lives and works in Montréal. He is an Associate Professor of Computation Arts at Concordia University and the Associate Director of the Technoculture, Art, and Games (TAG) Research Centre. Pippin is a prolific maker of videogames, producing work addressing everything from airplane safety instructions to contemporary art to the nature of games and videogame technologies. He has collaborated with diverse figures such as performance artist Marina Abramović, Twitter personality @seinfeld2000, and the International Federation for Human Rights. Pippin holds a Ph.D. in Computer Science from Victoria University of Wellington/Te Herenga Waka, with a dissertation that examined the mediation of values in videogames. He is a well-known figure in the independent and artistic videogame scenes, makes his source code and process documentation publicly available via his presence on GitHub, and his forthcoming book, The Stuff Games Are Made Of, presents an in-depth look at the significance of key elements of videogame creation, from computation and graphics all the way up to time and money. Pippin’s website, www.pippinbarr.com, organizes his diverse activities into a central location.

ARTISTIC STATEMENT

Pippin Barr’s work explores some of the paths-not-taken of videogame design, consistently focusing on ways in which videogames might express new and surprising ideas through their play. Central to his work is the idea of exposing the underlying nature of games themselves to his audience, from games that exhibit water technology for contemplation to large numbers of variations on simple games like Pong and Breakout that show how malleable game designs truly are. Much of Pippin’s work has also addressed the traditional art world as a way both to comment on that cultural mainstay and to use it to reflect on videogames as art; in this vein he has made work the reproduces pieces such as Marina Abramović’s The Artist Is Present or Gregor Schneider’s u r 1 as well as games that take on the museum form to place videogames front and centre, from his Art Game through to his current project v r $4.99. Throughout his career, Pippin has been most interested in making work that is relatable and funny as much as it might be intellectual or philosophical, and most of all making sure to bring the player in on the joke.

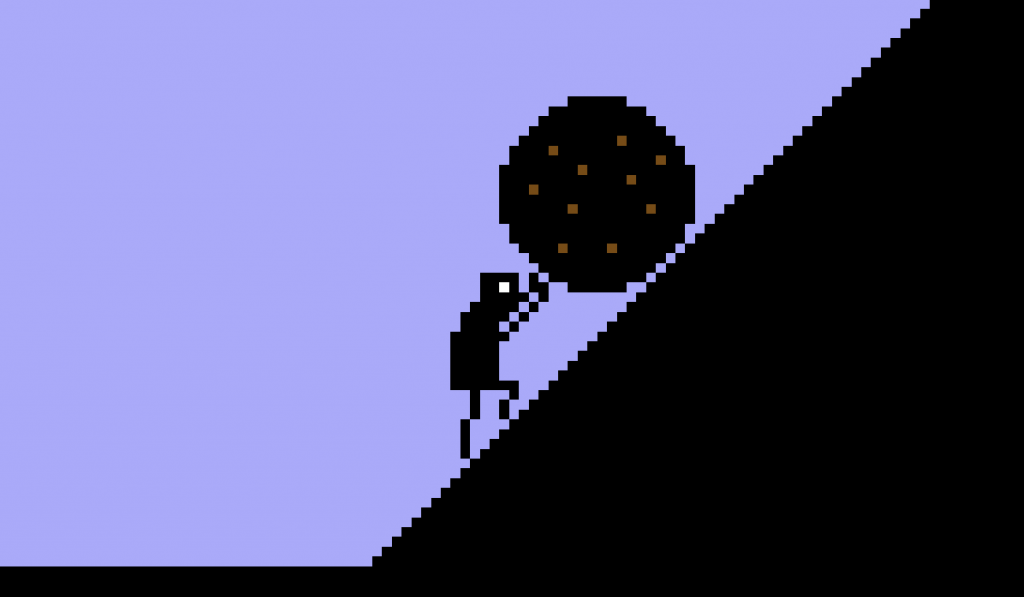

PROJECT STATEMENT

In 2011, I became fascinated by the idea of futility in videogames in place of the usual emphasis on agency and eventual success. To explore this, I chose the well-known story of Sisyphus, famously doomed by Zeus to push a boulder up a hill only to see it roll back down again, over and over. I made a videogame of the Sisyphus experience, duly recreating the mythological scenario, dooming the player, as Sisyphus, to push the boulder forever. That single game felt too minimal even for me, so I expanded the project into a set of five different punishment myths, bringing in Prometheus, Tantalus, the Danaids, and (less accurately) Zeno of Elea. The resulting game, Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment, provides players with the “opportunity” to step into the shoes of these glamorous punishments in a way that no mere retelling of the stories through speech or image can hope to offer: the video game is infinite in nature and will push the boulder back down the hill as often as you can bear to push it up.

The ideas covered in that first game felt especially relevant as a way to push back on traditional videogame design guidelines that emphasise, as above, agency and victory. I was enamoured enough that I chose to make a series of 12 (and counting) variations on the original. In each case, I’ve chosen either to present the myths in a new way – as games of chess, or traditional user-interface elements like sliders and checkboxes – or I’ve made videogame-oriented modifications to the way they play out – Sisyphus as a computer-controlled character, a two-player version in which the second player controls the boulder. As a broader suite of videogame experiences, the Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment series sheds light on videogame designs and desires in ways no single work can accomplish. Each game is in conversation with the others and with its players.

(Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment game, Pippin Barr, 2011)

Sandee Moore

ARTIST BIO

Sandee Moore is a white, settler, cis-woman who proposes to animate social relationships through personal exchange via artwork in media such as performance, video, installation, and interactive electronic sculpture. Moore has screened and exhibited across Canada (including The Surrey Art Gallery, The Art Gallery of Alberta, Plug In ICA, The Winnipeg Art Gallery, The Dalhousie Art Gallery, The Blackwood Gallery, and The Dunlop Art Gallery) and in Japan.

Her art criticism and scholarly texts have been published in various books, periodicals and newspapers.

She earned her B.F.A. (Honours) from The University of Victoria and M.FA. in Intermedia from The University of Regina. Following her education, Moore served as the Director of Video Pool Media Arts Centre (Winnipeg) and was an instructor at The School of Art at the University of Manitoba, before moving to Surrey, BC.

Moore currently makes her home on Treaty 4 Lands in Regina, SK, where she is employed as Curator of Exhibitions and Programming at the Art Gallery of Regina.

ARTIST STATEMENT

As an artist, I engage in the transformation of materials and the transformation of relationships. Through my artworks, I seek to create opportunities for audiences to engage in pleasure, relationships and creativity.

I use the tropes of capitalist exchange and popular culture to encourage audience engagement through methods of interaction that are familiar and nonthreatening. Many people are afraid of contemporary art but are comfortable and know how to interact with video games, smartphone apps and skateboard ramps

I create rewarding opportunities for creativity and sharing in my video games and other interactive electronic artworks. My artworks balance these enticements with an anti-game attitude, resisting the aesthetics and goal-oriented play that mark video games as entertainment. Video games are a powerful medium for empathy and experience, even if the experience is one of banality and boredom, replicating the fabric of our daily lives.

Indeed, the viewer in my works becomes active, whether strolling aimlessly, blowing on the wind or scrambling pop tunes through an analogue of skateboarding. More gratifying than the bombastic video game cliches, my low-stakes activities deflect stress and invite contemplation and conversation. Often I use games discursively to share intimate anecdotes and experiences, creating a bond and empathetic engagement with viewers.

PROJECT STATEMENT

The Mixer installation presents opportunities for viewers to be active and creative within the exhibition space. Several photo resistor sensors were embedded in the surface of the model of a 1/4 pipe. By moving over the surface of the ramp, the participant triggers a unique mix of audio samples from the video game Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2. I created an avatar to represent myself to players of the game, who could access stories from my history as a marginalized girl skater through playing the game. L’il Sandee, is a boy. The game only allows for the creation of male characters, which mirrored my experience of the homosocial skateboarding world.

Reflecting on this artwork over twenty years after I first created it, I became even more painfully aware of the innate sexism of the Tony Hawk Pro Skater video game series. Most of the female characters created by the game designers over multiple iterations of the video game are overtly sexy and scantily clad, while the sole female professional skateboarder represented in the game embodies an outright rejection (and devaluation) of femininity. I have turned statistics about gender representation in the five versions of Tony Hawk Pro Skater video game series into skateable objects. Instead of the original game’s drab concrete and plywood aesthetics, the level I have created immerses players in a feminized environment of pastel tones and confetti sprinkles.

(The Mixer: The Ultimate Sk8 Activity Centre, 2001, electronics, sculpture, household paint, modified video game, single-channel video. Photo courtesy of the Dunlop Art Gallery.)

SpekWork (Cat Bluemke and Jonathan Carroll)

ARTIST(S) BIO

Cat Bluemke and Jonathan Carroll research the concepts of work and play in contemporary entertainment media through their studio, SpekWork. They develop video games, virtual and augmented reality, and mobile applications that explore the connections between the subject of the user, worker, and player. The studio came together through our overlapping interests and backgrounds in teaching at the intersections of art, labour politics, and emerging technologies. They develop large or complex interactive media projects for exhibit at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, Toronto’s Nuit Blanche, and Rhizome & The New Museum’s Virtual Reality Art mobile application. Currently, SpekWork is developing the Digital Exhibitions Toolkit alongside the Mackenzie Art Gallery, to synthesize and publish some tools and techniques for exhibiting digital art on digital platforms.

ARTIST(S) STATEMENT

As a medium for art making, video games do not seem like an obvious choice – they are cumbersome to produce, often requiring large teams, dedicated technicians, and large amounts of money. When we started making video games as SpekWork, the struggle to overcome production challenges fascinated us, and quickly introduced us to wider discussions about work and labour in the tech industry. Seeing the initial organizing efforts of Game Workers United and the blossoming class consciousness of the gig economy has inspired the subjects we make games about, especially our Assassin’s Creed Art History series, which is a project about both the making of video games and the making of history. Our original reason for working with video games was their accessibility and popularity compared to the often intimidating and inscrutable art world fare we were accustomed to in grad school. Artists have always played a role in demonstrating the effects that new media have on our society and working in video games gives us the ability to learn about emergent technology and convey what we find to the audience in video game language they are familiar with.

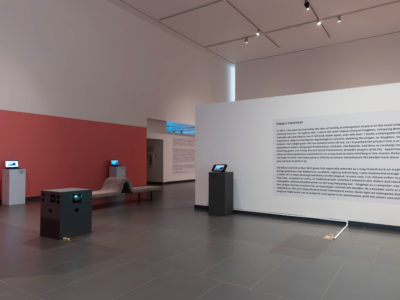

PROJECT STATEMENT

Media has always been our only access to history outside of personal memory, and the dominant media at the time, whether books, oral storytelling, film, or video games, contributes to how history is told and remembered. Assassin’s Creed Art History is a multimedia digital art project about the representation of history through video games and their narratives of technological progress. Using the Assassin’s Creed video game franchise as both material and subject, the project makes reference to the pop culture phenomenon to draw connections with broader themes including worker’s rights, police surveillance, and techno-solutionism. The project uses an interactive application, voice-over narration, and three-channel video installation that takes form as a three-panel altarpiece. This “altarpiece” installation includes three CNC-miled wooden frames that surround an LED monitor. Each panel plays a video, one after another; when a panel is not playing a video it will display a specific colourfield and icon combination. There are three videos in the triptych altarpiece, each video is an animation captured in a game engine (or “machinima”) that includes found footage, internet browser capture, and found 3D objects. The interactive application allows the audience to explore the 3D worlds created for the videos at their own pace.